Mar, 2016

For young Syrian children growing up in Lebanon’s scattered tent camps, life is uncertain at best.

Those who were born just before or just after the start of the crisis in Syria face a particularly daunting future.

Most of these kids barely remember Syria, if at all. Others – some 70% of the 60,000 children born in Lebanon – have no legal status. This new generation of Syrian children is homeless and stateless. The canvas rooftops and muddy fields of rural tented settlements are the memories they’ll associate with childhood. Meet some of the youngest Syrian refugees in Akkar.

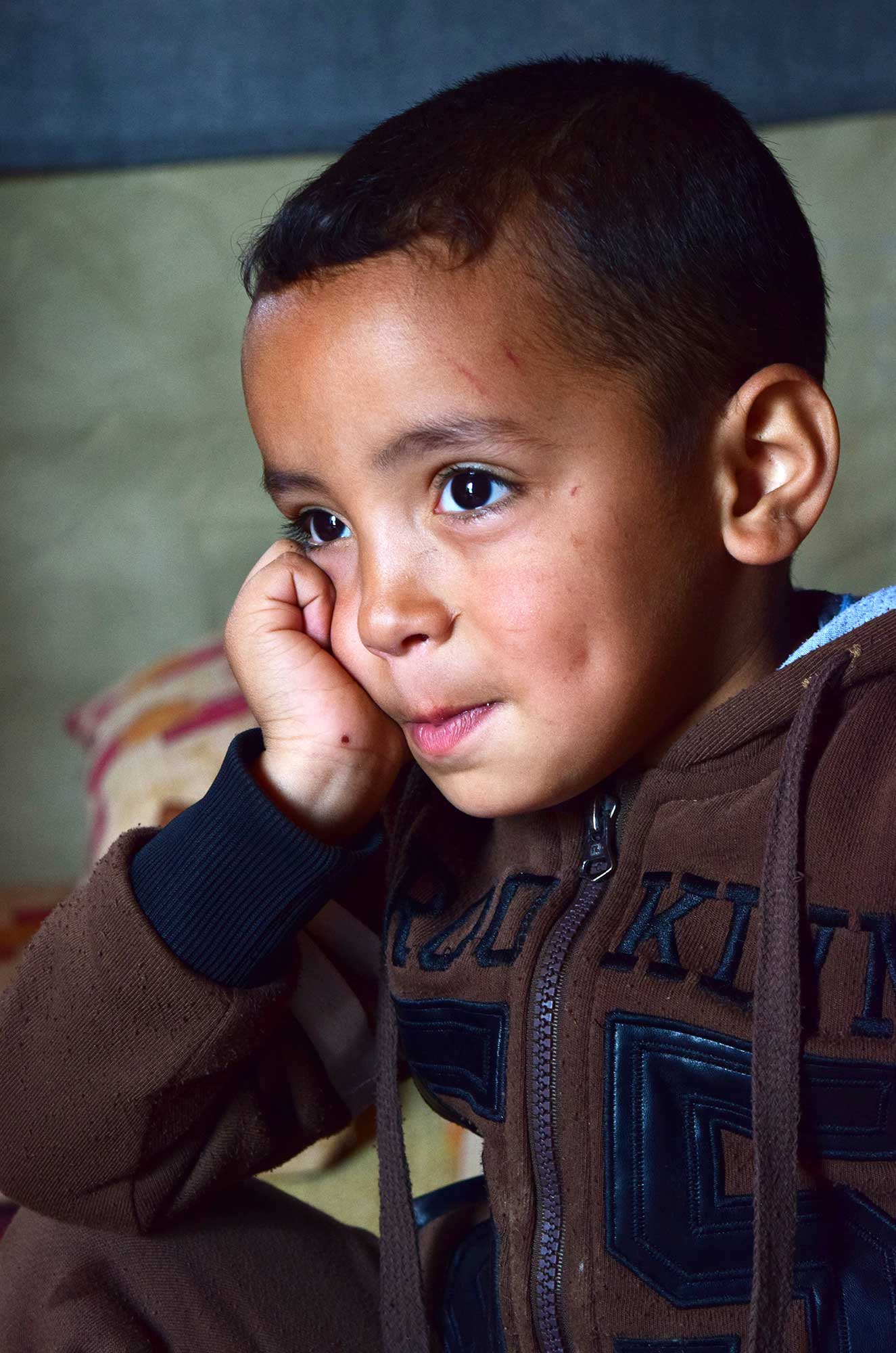

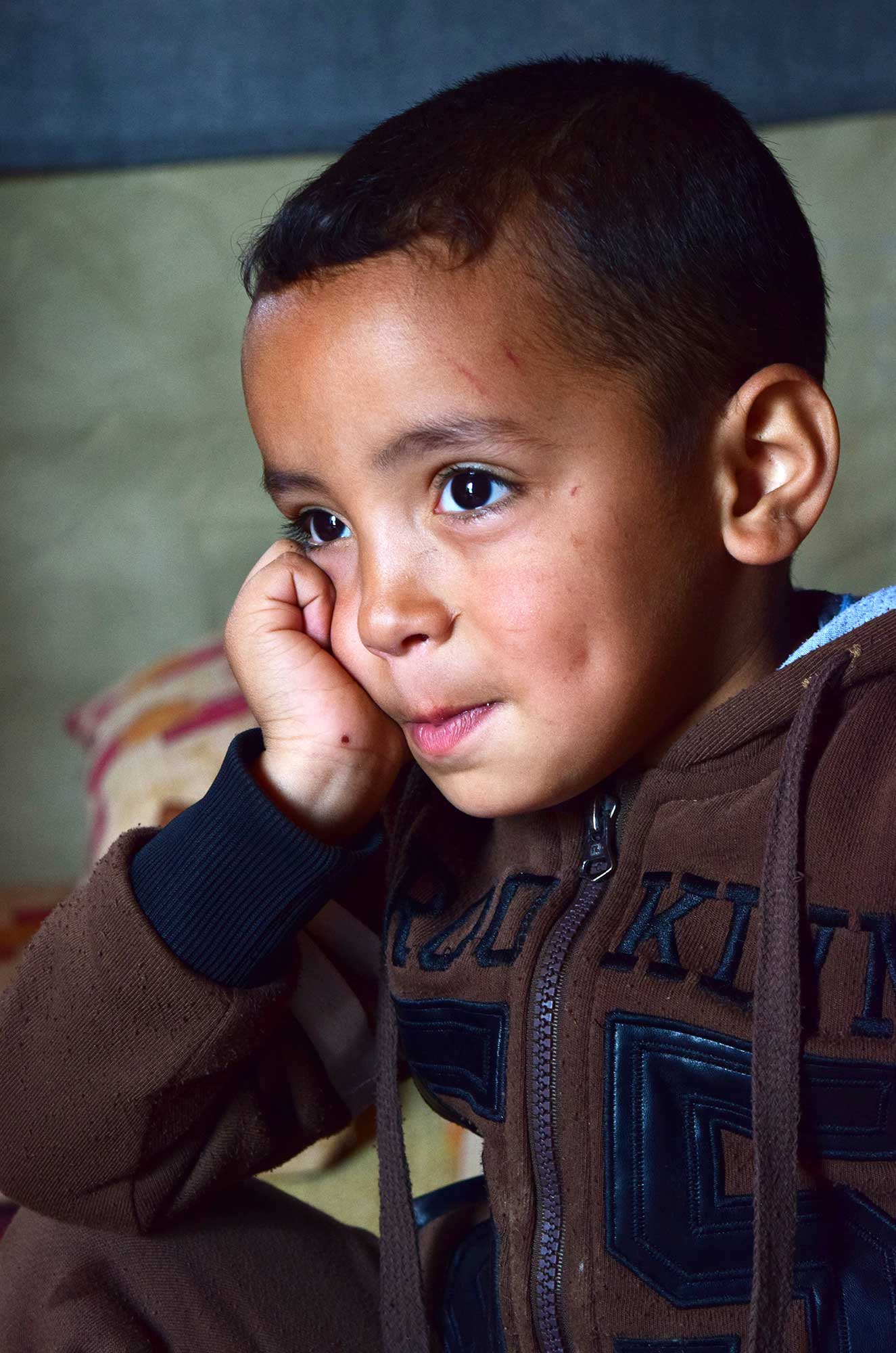

Mohammad’s Life Without Legal Status in Akkar, Lebanon

Young Mohammad’s sweet smile is a joy to see in the makeshift tented settlement where he lives with his mother, father and baby sister, Aicha. Because of the obstacles to obtaining a birth certificate during his family’s displacement, Mohammad is deprived of a legal status in Lebanon. This prohibits him from accessing formal education, public hospitals or any other state provided services. Legally, Mohammad does not exist.

While older camp residents, including his parents, look back on Syria longingly, Mohammad doesn’t have any memory of Syria at all. His mother Nisrine tells him all about life in Syria and describes meticulous houses and schools in their old neighborhood in Homs, but Mohammad can’t imagine it. “Mom tells me that Syria is beautiful, but I like it here more,” he says.

Mohammad goes to an educational facility next to the tented settlement, where he attends non-formal English and Arabic classes. He also plays soccer in the sports field Anera recently renovated to give the kids in nearby camps the chance to play safely with their friends.

Without recreational spaces like this, there’s not much for Syrian children to do in Lebanon. Most days, Mohammad spends a lot of time with his little sister Aicha, who is one year old. He and his four best friends in the camp take turns holding baby Aicha.

“Children are constantly bored,” says Nisrine. “In Syria, we had more recreational spaces, big houses, gardens and yards. Here, I feel like we are in a prison.”

“All we want to do is go back home,” she adds.

Mohammad, on the other hand, is not yet aware of the hardships he’ll likely face when he gets older. He doesn’t know that if he gets sick, he might not be able to go to a hospital. He loves school, even if he only attends a few non-formal classes, and wants to become a pilot.

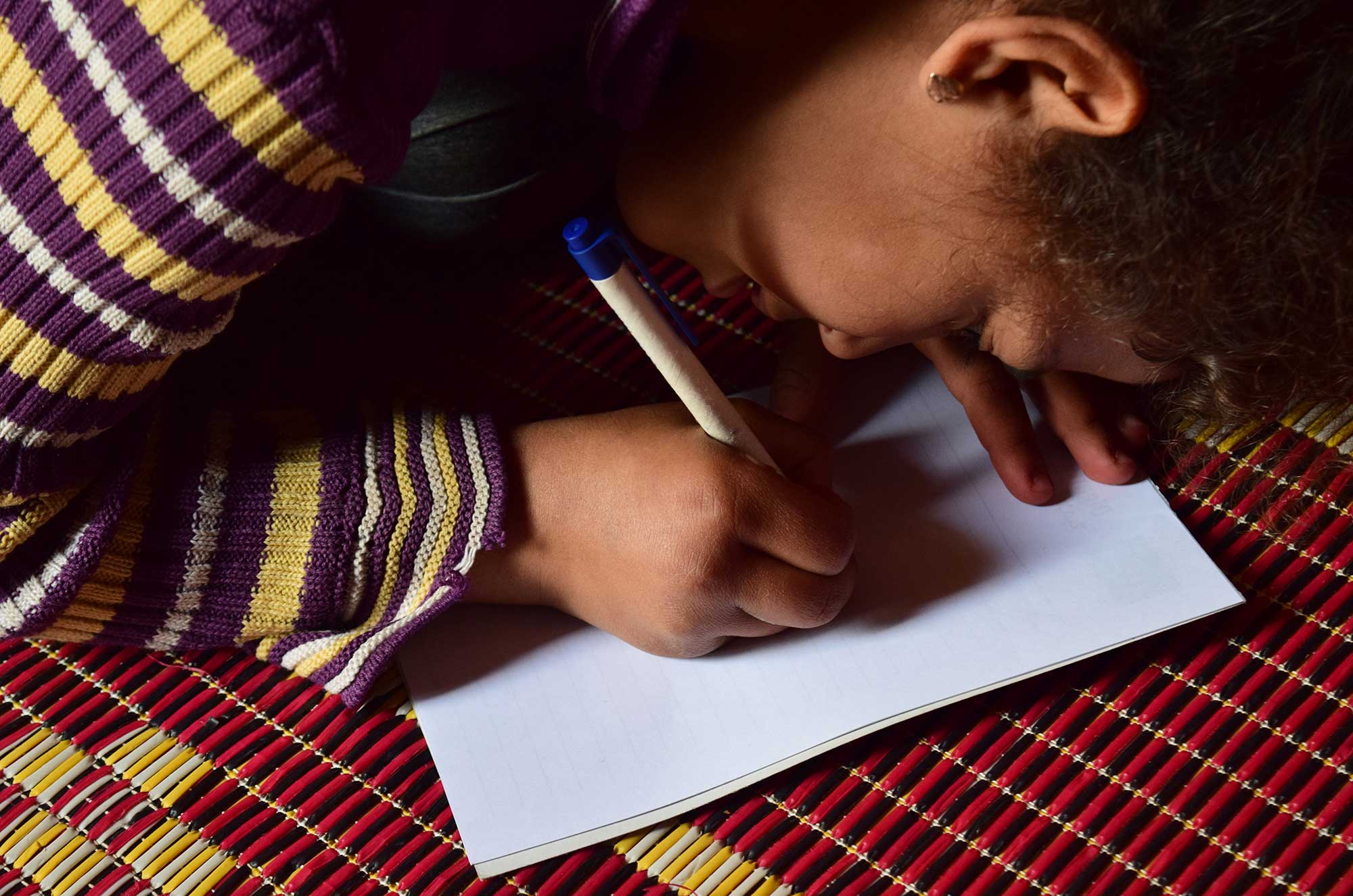

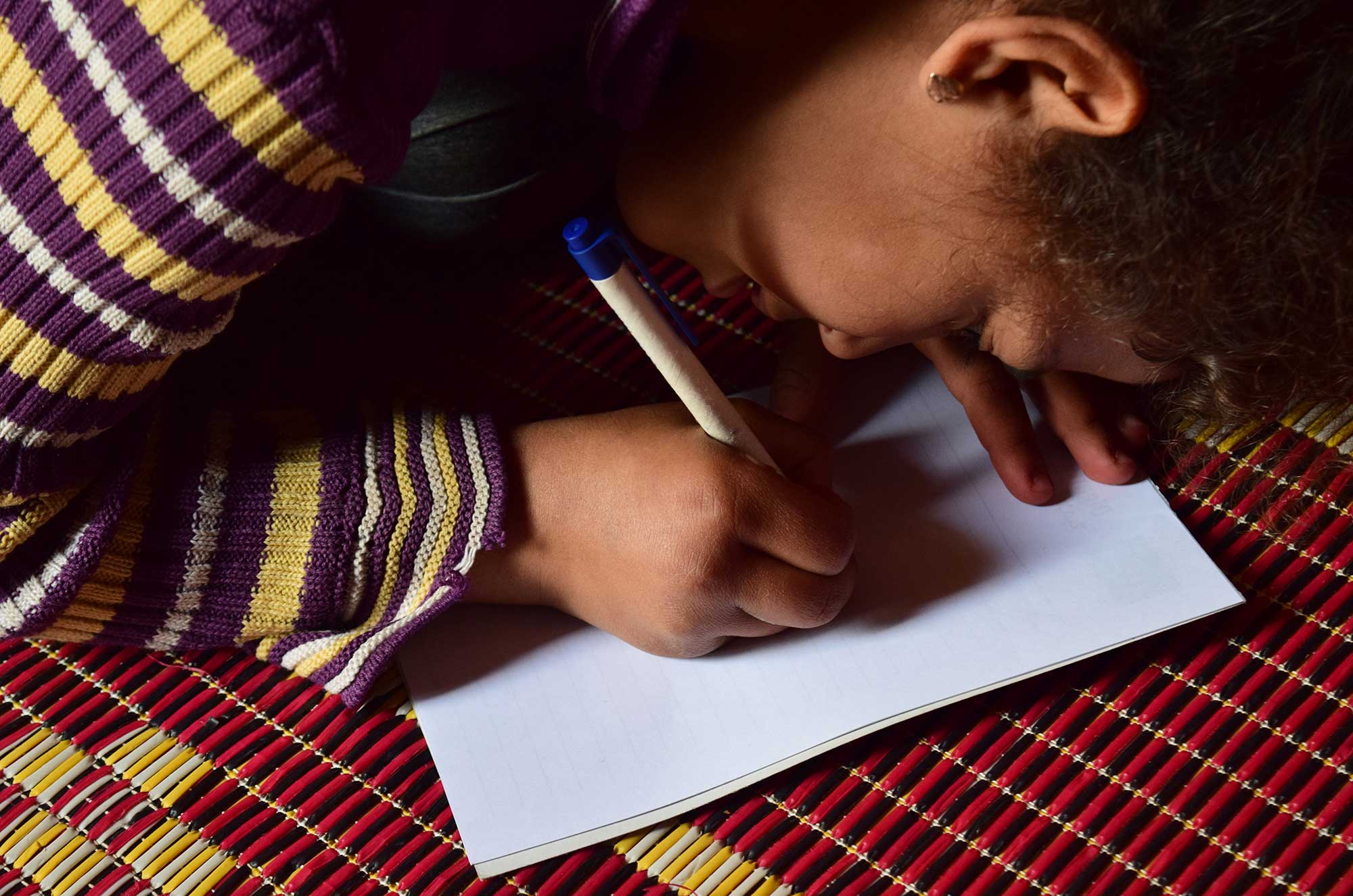

Marwa and the Future of Syrian Children

Marwa, an outgoing seven year old, acts as a young ambassador to the tented settlement. She welcomes humanitarian relief workers and journalists who find their way to the camp.

Marwa’s family came to Lebanon when she was two. They left their home in Homs when heavy shelling hit their house.

“I don’t remember anything of Syria, I was very little when we came here,” says Marwa. “But here [at the camp], it is like a village, everyone knows everyone.”

Marwa also goes to school near the camp. “I made some friends that I go to school with everyday and then we go play around the play field,” she says. “I don’t like school very much, but I am still better than my siblings and at least I manage to get passing grades.”

Even though she doesn’t like school very much, Marwa already has a plans for a future career in teaching. “When I go back to Syria – because this is where we come from, right – I want to become a school teacher.”

Marwa sits down on the mat inside her family’s tent to work on a drawing. She starts to draw a house, but can’t finish it.

“I cannot draw a house, I will draw a tent instead,” she says. “I don’t know what a house looks like.”